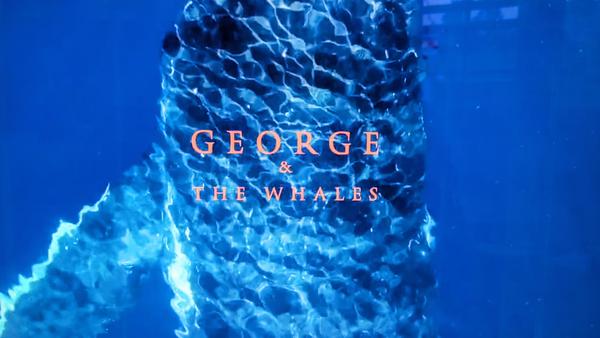

There is a short video about the whales in Tonga. The narrator introduced himself with a long, tribal name that I forgot as soon as he said it. But he was generous.

"You can call me George."

I like learning people's names and feel embarrassed when I struggle.

Having an easier way to address them is a relief.

George belongs to a people who have made an historic shift. They used to kill the whales, which brought those marvelous creatures to the precipice. There were a few dozen left. But when I was in college, the King of that land declared hunting whales to be illegal.

I was of course oblivious to such events, being focused on psychology class and my social life. But in the years since,

the whales have gradually increased in numbers. Now there are several thousands of these majestic behemoths, who travel from the Antarctic to the warm waters of Tonga.

In the absence of eating the flesh of whales, the people who put down their spears found another way to interact. They learned how to swim with the whales, and invited tourists to enjoy it, too.

It seems likely that such a change in their tradition was scary.

Perhaps they feared that their children would starve. The momentum of hunting is incompatible with the curiosity and even vulnerability of jumping into the whale's domain. Yet someone did. Others followed. There were probably heated conversations and even broken friendships. Slowly the tide turned.

Somehow it feels hopeful to me, as I watch a world with its own versions of stabbing. There are signs of vulnerability coming up for air. Laughter, tears from a young

man for his father, words like "empathy" being spoken by a female politician.

I have even learned how to say her name.

"They will beat their swords into plowshares and their spears into pruning hooks. Nation will not take up sword against nation, nor will they train for war anymore." Isaiah 2